Note from Rebus: A version of this story appeared in SLANT in 1987. It has been rewritten several times. In 2011 a version similar to this one was published by the James River Film Journal.

The avalanche of eye-opening movies that tumbled onto the somewhat cocky, painfully local kid who was the Biograph's first manager was an education for him. That, with some of the new associations Rea made, was an intensive schooling in popular culture. This story spotlights a hell of a prank and some behind-the-scene aspects of the Biograph’s single-auditorium history, before its 1974 makeover into a twin cinema.

The Biograph opened in an era that seemed ready to give the baby boomers who were becoming adults whatever they wanted.

*

My first good look at what was to become the Biograph Theatre was in July of 1971. Having gotten a tip from a friend that the DeeCee-based owners were considering the hiring of a local manager, I went to the construction site chasing the opportunity.

That day I met David Levy, one of six men who owned the repertory cinema operation that would be housed in the cinderblock building going up at 814 West Grace Street. Of the six, Levy would prove to have the deepest knowledge of film history, as well as the most hands-on knowledge of how to run a movie theater. At 33, Levy, a Harvard trained lawyer, was 10 years my senior.

A couple of months later I was offered what I saw as the best job in my neighborhood, the Fan District. Without hesitation I decided to quit my job at WRNL, a local radio station. The adventure that followed surely went beyond any expectations I might have had about becoming the manager of the Biograph Theatre.

On the evening of February 11, 1972, the venture was launched with a gem of a party. The feature presented that evening was a delightful French war-mocking comedy — “King of Hearts” (1966); Genevieve Bujold was dazzling opposite the droll Alan Bates.

In the lobby, with its cinemascopic view of Grace Street through a glass front, the dry champagne flowed steadily. A trendy art show was hanging on the lobby walls. Hundreds of equally trendy invited guests were there. The local press was all over what was an important event for that bohemian commercial strip, just a stone's throw from the Virginia Commonwealth University campus.

My stint at the Biograph lasted until the summer of 1983. It would be 37 years before the next new cinema would open in Richmond — Movieland, in February of 2009.

*

During the 1960s, college film societies thrived. Knowing film was cool; it could get you laid. By the 1970s, many of the kids who had grown up watching old movies on television had learned to worship important movie directors.

The fashion of the day elevated certain foreign movies, selected American classics, a few films from the underground scene, etc., to a level above most of their more accessible Hollywood counterparts. Mixed and matched in double features and packaged into little festivals, such was at the heart of a repertory cinema’s style. In that pre-cable TV age, much of the current-release domestic product was viewed by the film aficionado in-crowd as laughingly naive or hopelessly corrupt.

Although none of them had any experience in Show Biz a group of five men, who were all about Levy's age, opened Georgetown’s Biograph Theatre (1967-96) in 1967. They were smart guys who caught a wave. A few years later those same owners (plus one more guy) were looking to expand. In Richmond’s Fan District they thought they had spotted the perfect situation for a second repertory-style cinema in a neighborhood that was being touted then by local boosters as about-to-blossom-into-another-Georgetown.

Local players, filthy rich Morgan Massey and deal-maker Graham “Squirrel” Pembrooke, put up the building from scratch for the Georgetown group. Significantly, Pembroke managed to get a 20-year lease for $3,000-a-month rent guaranteed by a federal program for at-risk neighborhoods, in case the concept didn’t fly.

Thus, when the Biograph closed in 1987 the building’s owners were then able to collect the rent from Uncle Sam until 1992.

Knowing they could walk away easily, if the business fizzled, the new Biograph’s creators — chiefly Levy and Alan Rubin (a geologist turned artist) — inked the deal and borrowed money to buy used seats and projection booth equipment, which included ancient Peerless carbon arc lamps to back up a pair of rugged Simplex 35 mm projectors.

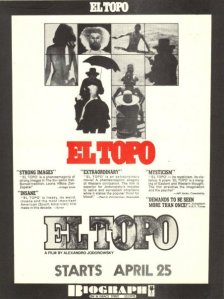

The Biograph’s programs, printed schedules with film notes, covered about six weeks each. Program No. 1 was heavy on documentaries, featuring the work of Emile de Antonio and D.A. Pennebaker, among others. Also on that program were several titles by popular European directors, including Michaelangelo Antonioni, Costa-Gavras, Federico Fellini, and Roman Polanski.

After the opening flurry, with long lines to every show, it was surprising and disappointing when the crowds shrank dramatically in the third and fourth months of operation.

As VCU students were a substantial portion of the theater’s initial crowd the slump was chalked off to exams and summer vacation. In that context the first summer of operation was opened to experimentation aimed at drawing customers from beyond the neighborhood.

The brightest light in our mix of celluloid offerings was a project I had been put in charge of developing — Friday and Saturday midnight shows. Their popularity was waxing.

By trial and error we learned it took an offbeat movie that lent itself to promotion; early successes were “Night of the Living Dead” (1968), “Yellow Submarine” (1968), “Mad Dogs and Englishmen” (1971), and an underground twin bill of “Chafed Elbows” (1967) and “Scorpio Rising” (1964).

With significant input from the theater’s promotion-savvy assistant manager, Chuck Wrenn, off-the-wall ad campaigns were designed in-house to set the tone for the somewhat anti-establishment movies that seemed to perform best at the box office. There were two essential elements to those promotions:

1. Wacky radio spots had to be created and run on WGOE, a popular AM station aimed directly at the hippie listening audience.

2. Distinctive handbills were posted on utility poles and bulletin boards, and in shop windows in high-traffic locations.

Dave DeWitt, now the widely read guru of hot food, produced the radio commercials, many of which were considered to be rather humorous in their day (if I do say so myself). In his studio, Dave and I frequently collaborated on the making of those spots over six packs of Pabst Blue Ribbon.

On September 13 a George McGovern-for-president benefit was staged at the Biograph. Former Gov. Doug Wilder, then a state senator, spoke. We showed "Millhouse," a documentary that put President Richard Nixon in a bad light. Yes, I had been warned by some well-meaning people, supposedly in the know, that taking sides in politics was dead wrong for a show business entity in Richmond. Especially, taking the liberal side.

Happily, my bosses and I blew such advice off and the theater was used over the years lots of times to raise money and awareness for causes.

Also in September “Performance” (1970), an overwrought but well-crafted musical melodrama — starring Mick Jagger — packed the theater at midnight a couple of weekends in a row. Then a campy, docu-drama called “Reefer Madness” (1936) sold out four consecutive weekends.

To follow “Reefer Madness” what was then a little-known X-rated comedy, “Deep Throat” (1972), was booked as a midnight show. As the feature ran only an hour, master prankster Luis Buñuel’s surrealistic classic short film, “Un Chien Andalou” (1929), was added to the bill, just for grins.

Although it should be noted that like "Deep Throat," Buñuel’s first film was also called totally obscene in its day, this may have been the only time that particular pair ever shared a billing ... anywhere.

A few weeks after “Deep Throat” began playing in Richmond, a judge in Manhattan ruled it was obscene and suddenly the national media became fascinated with the film. Its star, Linda Lovelace, appeared on network TV talk shows. Watching Johnny Carson tiptoe around the premise of her celebrated “talent” made for some giggly moments.

Eventually, to be sure of getting in to see the midnight show, patrons began showing up as much as an hour before show time. Standing in line on the sidewalk for the spicy midnight show turned into a party. There were nights the line resembled a tailgating scene at a pro football game. A determined band of Jesus Freaks frequently stood across the street issuing bullhorn-amplified warnings of hellfire to the jolly set waiting in the midnight show line that stretched west on Grace Street.

Playing for 17 consecutive weekends, at midnight only, “Deep Throat” grossed over $30,000. That was more dough than the entire production budget of what was America’s first skin-flick blockbuster.

The midnight show’s grosses conveniently made up for the disappointing performance of an eight-week package of venerable European classics, including ten titles by the celebrated Ingmar Bergman. The same package of art house workhorses played extremely well up in Georgetown, underlining what was becoming a painfully underestimated contrast in the two markets, just 100 miles apart.

Washington was a great movie town, Richmond was not.

Even more telling, over the spring a series of imported first-run movies crashed and burned. The centerpiece of the festival was the premiere of the Buñuel masterpiece, “The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie” (1972). In what Levy and I then regarded as a coup, gambling it would win the award, we booked it in advance to open in Richmond two or three days after the 1973 Oscars were to be handed out. We guessed right, it took the Oscar for Best Foreign Film, but it flopped in Richmond, anyway.

Management was more than bummed out, we were shocked.

Money had been put up in advance to secure a print, which was in demand because it was doing brisk business in most other cities. The failure of this particular booking and the festival that surrounded it forced a serious reassessment of what had been the original plan.

To stay alive Richmond’s Biograph needed to make adjustments.

After much fretting on the phone line between “M” Street and Grace Street the Faustian deal was struck — another film from the director of “Deep Throat,” Gerard Damiano, was booked. However, this time the film’s distributor imposed terms calling for “The Devil in Miss Jones” (1973) to play as a first-run picture at regular show times, rather than as a midnight-only attraction.

At this point no one could have anticipated what we were setting in motion by agreeing to expand the availability of “adult movies” beyond the midnight hour. For the first time, the promotional copy for an XXX-rated feature was included on a Biograph program and in newspaper ads.

Then an aggressive young TV newsman took Biograph Program No. 12 to Richmond's new Commonwealth’s Attorney, Aubrey Davis. The reporter asked Davis what his office was going to do about the Biograph’s brazen plan to run such a notorious film, especially in light of the then-freshly-minted Miller Decision on obscenity by the Supreme Court. (Miller basically allowed communities to set their own standards for obscenity.)

Eventually, the provocateur got what he wanted from the prosecutor — who had been on the job for just a month — a quote that would fly as an anti-smut sound bite. The other local broadcasters jumped on the bandwagon the next day. By the mid-summer evening “The Devil in Miss Jones” opened in Richmond it had already become a well-covered story.

Every show sold out and a wild ride began: Matinees were added the next day. On the third day all the matinees sold out, too. The fourth day the WRVA-AM traffic-copter hovered over the Biograph in drive time, giving live updates on the length of the line waiting to get into the theater. The airborne announcer helpfully reminded his listeners of the remaining show times for that night.

Well, that did it!

The following morning a local circuit court judge asked for a personal look at what was clearly the talk of the town. Management cooperated with his honor’s wishes and the print was schlepped down to Neighborhood Theaters’ private screening room, at 9th and Main Streets, for the convenience of the judge. We assumed he wanted to avoid being seen by curious reporters entering the wicked Biograph.

As Judge James M. Lumpkin admittedly hadn’t been out to see a movie in a theater since sometime in the 1950s, this particular comedy stag film rubbed him in the worst way. Literally red-faced after the screening, the outraged judge looked at Levy and me like we were from Mars, maybe Pluto.

Lumpkin promptly filed a complaint with the Commonwealth’s Attorney and set a date for issuing a Temporary Restraining Order, in an attempt to halt further showings as soon as possible.

The next day a press conference was staged in the theater’s lobby to make an announcement. Every news-gathering outfit in town bought the premise and sent a representative. They acted as if what was obviously a publicity stunt was actually 24-carat news, because it served their purpose to play along. After DeWitt — who was then representing the theater as its ad agent — laid out the ground rules and introduced me to the working press, I read a prepared statement for the cameras and microphones.

The gist of it was that based on demand — sellout crowds — the crusading Biograph planned to fight the TRO in court. Furthermore, the first-run engagement of “The Devil in Miss Jones” would be extended — it would be held over for a second week.

During the lively Q & A session that followed, when Dave scolded an eager scribe for going too far with a follow-up question, it was tough duty holding back the laughing fit that would surely have broken the spell we trying to cast over the reporters.

The TRO stuck, because Lumpkin still had all the say-so. “The Devil in Miss Jones” grossed about $40,000 in the momentous nine-day run the injunction halted.

Technically, the legal action was against the movie, itself, rather than anyone at the Biograph. Which obviously suited me just fine. The trial opened on Halloween Day. Judge Lumpkin, whose original complaint to the Commonwealth’s Attorney had set the process in motion, served as the trial judge, too.

Objections to that quizzical affront to justice fell on Lumpkin’s stone cold deaf ears.

On November 13, 1973, Lumpkin put all on notice: If you dare to exhibit this “filth” to the public, then stand by for certain criminal prosecution. So it was that “The Devil” was banned by a judge in Richmond, Virginia.

The plot to answer the judge's decree was hatched in early January of 1974 in my office, next to the projection booth on the second story. Having finished the box-office paperwork, your truth-telling narrator was browsing through a stack of newly acquired 16mm film catalogs and probably enjoying a cold PBR longneck. As it was after-hours, the scent of recently-burned marijuana may have been in the air when a particular entry — “The Devil and Miss Jones” — jumped off the page.

It was instantly obvious that the title for that 1941 RKO light comedy had been the inspiration for the X-rated movie’s title — “The Devil in Miss Jones.”

It should be noted that the public had yet to be subjected to the endless puns and referential lowbrowisms the skin-flick industry would eventually use for titles. This was still in what might be called the seminal days of the adult picture business.

The plan called for using the upcoming second anniversary as camouflage. DeWitt and the theater’s resourceful assistant manager, Bernie Hall, were in on the early scheming. Then, in a deft stroke — suggested by Alan Rubin — a Disney nature short subject, “Beaver Valley” (1950), was added to the birthday program.

The stunt’s biggest problem was security. The whole scheme rested on the precarious notion that the one-word difference in the two titles, which spoke of the Devil's proximity to Miss Jones, wouldn’t be noticed. It was something like hiding in plain sight. The staff fully understood that the slightest whiff of a ruse would mean our undoing. Thus, absolutely no one outside our group could be told anything.

No one.

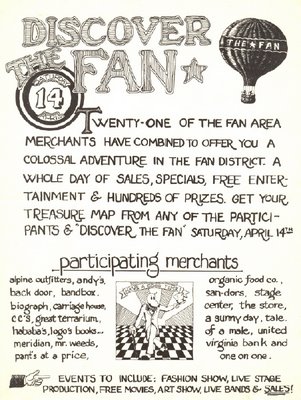

Subsequently, the theater announced in a press release on DeWitt’s letterhead that its second anniversary celebration would offer a free admission show. The titles, “The Devil and Miss Jones” and “Beaver Valley,” were listed with no accompanying film notes; free beer and birthday cake would be available as long as they lasted.

Somehow, a rumor began to circulate that the Biograph might be out-maneuvering the grasp of the court’s decree by not charging admission. The rumor found its way into legit print — the street gossip section of The Richmond Mercury. That was sweet.

The busier-than-ever staff fielded all inquires, in person or over the telephone, by politely reciting the official spiel, “We can only tell you the titles and the show times. Yes, the admission will be free. No further details are available.”

The evening before the event the phones were ringing off the hook. The anticipation was fun, reporters were snooping about. One, in particular, seemed to be clawing his way toward the key. In the lobby, as I manned my familiar post at the turnstile, he said to me, “It has to have something to do with the title.”

He was getting too close; to fend him off I had to take a chance. So I told the guy that what was going to happen the next day would be a far better news story than the story of spoiling it the day before ... if there really was a trick to it.

Gambling that it would work, I asked him to leave it alone and trust that once it all unfolded he wouldn't regret it. Fortunately, the newsman said OK and kept his word. His identity must remain a secret.

Up until the box office opened no one else outside our tight circle appeared to have an inkling of what was about to happen. Amazing as it may sound, the caper’s security was airtight. It was absolutely beautiful teamwork!

The line for the Biograph's special anniversary screening/party began forming before lunch. As the afternoon wore on, with thousands of people lining up, it was suggested to me more than once that we could eventually have a riot on our hands. What would happen if we lost control of the situation?

Nobody knew. That’s what made it so exhilarating!

The box-office for the 6:30 p.m. show opened at 6 p.m. By then the line stretched more than three-quarters of the way around the block. It took every bit of a half-hour to fill our 500-seat auditorium. No doubt, we turned away at least six or seven times that number.

The sense of anticipation in the air was electric as the house lights in the auditorium began to fade. Outside, on the sidewalk, hundreds of people stayed in line for the second show at 9 p.m.

As the prank unfolded in layers only about a third of the crowd stayed through both movies. Afterward, there were lots of folks who said it was the funniest thing that had ever happened in Richmond. Of course, a few hard-heads got peeved. But since admission had been free, as well as the beer and cake, well, there was only so much they could say.

The rush that came from living in the eye of that day’s storm was intense, to say the least. Gloating over the utter success of the gag, as the staff and assorted friends finished off the second keg, was as good as it gets in the prank business.

Meanwhile, thoroughly amused reporters were filing their stories on the hoax. The next day wire services and broadcast networks picked up the story. And, the Biograph Theatre returned to business as usual with an Andy Warhol double feature.

*

A few days later NPR’s All Things Considered went so far as to compare the Biograph’s prank to Orson Welles’ mammoth 1938 radio hoax. Which was fun to hear. Fortunately, I had the good sense to tell the interviewer that in comparison our stunt was "strictly small potatoes."

Later that same month the staff went back to work on “

Matinee Madcap,” a 16mm film project in production. Trent Nicholas, then one of the theater’s ushers and later an assistant manager, shared the directing credit with me. The rest of the staff and several of the Biograph’s regulars appeared as players. The plot, calling for a good deal of slapstick chase-scene footage, conveniently set all the action in the movie theater.

Although post-prank life seemed to fall back into a familiar routine, big changes were on the horizon. With Watergate revelations in the air and the Vietnam War winding down, the interest in politics and social causes on American campuses began to evaporate. VCU was no different. In the spring of 1974 “streaking” replaced anti-war demonstrations as college students’ favorite expression of defiance.

Six months after the theater’s second anniversary splash, the same month that Richard Nixon resigned the presidency, the Biograph closed down for a month to be converted into a twin cinema. With construction workers toiling 24 hours a day that accomplishment

remains a story of extremes, all to itself. Some of them were gobbling

up white crosses like they were Sno-Caps or Jujyfruits. The

middle-of-the-night Liar's Poker games with 15 guys playing were

outrageous. But all that is a story for another day.

After the construction work was completed, with two booths and a hallway

between them, automating the change-overs from one 35mm projector to

the other was essential to controlling costs. Among other things that

necessitated switching to Xenon lamps -- high intensity bulbs that could

be ignited by switches -- to replace our out-of-date, manually-operated

carbon arc lamps.

Not long after that change David Levy split with his other partners. That left four of the original six Richmond Biograph owners still on board. Levy (who died in 2004) went on to distribute alternative films regionally, plus he bought and operated The Key on Wisconsin Avenue in Georgetown.

The manager’s job at the Biograph in Richmond became more complicated with two screens to fill. The whole repertory cinema mission was becoming blurred with the passing of time. Following the accumulation of 1974's events, a year of many changes, much of what had appeared to be among life’s absolutes became steadily less clear for the dreamer who had started out believing he could change Richmond by screening great films.

As the edgy punk style began replacing the hippie culture that had ruled the Grace Street strip for the better part of a decade, none of us who were working at the Biograph Theatre had an inkling that the zenith of the repertory cinema era, nationally, was in the rear-view mirror.

In the spirit of a postscript, here's a personal note:

At the press conference in the Biograph’s lobby, I asked for the public to weigh in. Send me your opinions, I entreated my local news audience. I framed it with questions like: Are we right or wrong to fight the Temporary Restraining Order? Is this a freedom of speech issue, or not? Who should decide what movies you can see?

Eventually I got over 100 letters, cards, etc. Some were mailed to the theater, others dropped off. Most were supportive but not all. There were a few letters that were quite entertaining. So, I collected the best of them in an cardboard box (I don't remember what brand of candy came in the box), figuring they might be useful down the road.

Into the same box went clippings about the tumultuous run of “The Devil in Miss Jones” and the Biograph’s news-making days in court. Later on, several stories about the prank from various newspapers from out of town were tossed in.

Then, about a year after the hoopla, the prankster suddenly changed his mind. Caught up in a bad mood — caused in some part by a slipped disc that was dogging me at the time — I sat in my office festering over the idea that no matter how hard I ever worked to put over the greatest art films, most people in Richmond would simply ignore them.

After the twinning of the theater I couldn't watch the movies through a window in my office, anymore. That window was a much-missed advantage to the one-screen setup. A year of prank-driven attaboys had suddenly added up -- I‘d had my fill of it. The annoying thought of being known mostly for my connection to a somewhat creepy, even pretentious, porno movie wasn't setting well with me.

At 26, perhaps I already suspected the Terry Rea of the future might develop an embarrassing tendency to wallow in nostalgia. Just like that, I decided to play a time trick on my future-self by deliberately throwing away those artifacts I’d surely want back … some day.

Perhaps the bitter need my precious Biograph had developed to show trashy movies, in order to be allowed to also show important movies, grossed me out a little extra on that particular winter’s afternoon.

Walking away from the dumpster and crossing the cobblestone alley behind the theater, I laughed at what I had just done; the moment is still vivid.

When I think back about what an effort it took just to keep the Biograph Theatre's doors open in those days, it seems like it was all an elaborate stunt … pranks for the memories.

All rights reserved by the author.